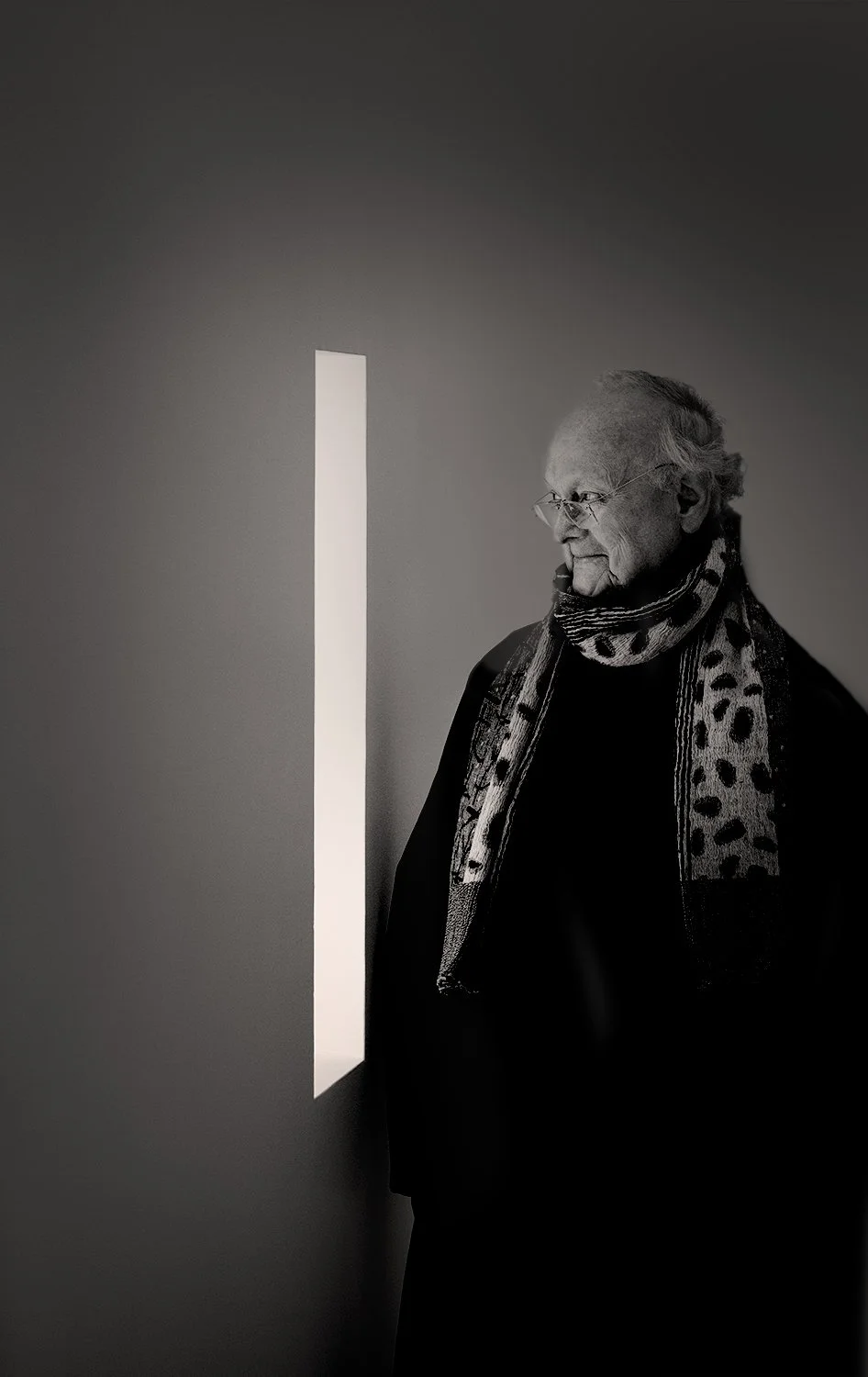

Glenn Murcutt reflects on more than 55 years of practice…

Photo credit: Stuart Spence

On the occasion of his 89th birthday, Glenn Murcutt AO shares reflections on more than five decades of architectural practice.

"The past 55 years in practice has taken many turns. Some very good. Some very difficult. Some nearly destroyed me. But I got through all of them. My greatest achievement is that I’ve survived 55 years"

55 years has gone so fast. My first 30 years seems to take a long time, but the next 50 years is really so fast, it’s not 50 years at all.

I remember driving over the Sydney Harbour Bridge the day I graduated. I was so happy I got through, and I was able to start preparing to be an architect. I remember thinking to myself: here I am at 23 years of age and - another 30 or 40 years - is such a long time ahead. You can make so many mistakes in that time, and it’s so hard to do good work. I got a bit frightened. There have been periods in that time when I’ve had great doubts about my ability to design; my ability to pursue a goal that I knew was to do good work.

I wanted to do what Thoreau said: “to do ordinary things extraordinarily well”. My aim was never to be in the situation where my work drew attention. The reality is that I’ve been through some very tough times. I’ve been through recessions and I’ve hung on. In one recession, I wasn’t able to afford to re-registered the car and I took a bus to the site. I got off the bus stop before and walked to the site, so the builder didn’t know I didn’t drive.

But 3 months later the work started to return, and I was taught one must hang on. In spite of everything showing you’re heading for failure - hang on.

I pursued what I felt was important in architecture, not what was important to my bank balance, My bank balance has never been commensurate with my work! But to do things really well, takes a lot of time. One has to be prepared to work on a project and take it to fulfilment and realise, even then, it’s not good enough. I have completed working drawings of a job, and thought to myself: “I know a better solution”. And I found that better solution very quickly. I then completed those working drawings, and when I met the client, I took the working drawings of the 2nd solution. I said to him: “you must be shocked”. But he was delighted, and that was very fortunate. At one stage in my practice, I lost confidence completely. I said to my wife: “I know what good architecture is. I have a feeling I just don’t know how to do it.”

But I just received a travel grant.

I thought: I can’t go now. I’ll ask if I can delay it for a year. That will give me time to think about what I’m going to do and who I might see who might give me some sort of clue what my difficult is. I thought of various people, and the one who came up as the strongest was José Coderch, the great Spanish architect. And to see the great Maison de Verre.

These were two major ambitions of mine.

But this also included Craig Elwood. And I visited the work of Mies. I hadn’t visited any of their works on my previous trips, and I thought it was time to see the work because I had such a sympathy for it.

Craig Elwood

I spent a wonderful day with Craig Elwood. It was a beautiful day and he sent me off with a book on his work.

But I asked Craig: “how do you keep the sun out of your work in the summer time?” I thought he’d come back with some clever answer like the glass being smart glass - some sort of fantastic glass. He looked at me as if it was the most stupid question anyone had every asked him. He said: “Why, we air condition it!” Then I said; “you’ve got a timber building here and I can see some gaps. How do you stop the water getting in?” And he said: “we pressurise our buildings so we push the air out, and the water doesn’t come in”.

I said to myself: “I admire what you’re doing. But that is not the direction I’m going.”

Craig was incredibly important to show what I should not be pursuing - the minimal sort of architecture that was being presented. It had inherent dangers for me, and for my country.

Maison de Verre

It was not until I got to Paris to see the work of Maison de Verre that I was totally bowled over. Suddenly, in a period of post modernism that was getting rid of modernism. Here was a being designed in the mid 1920’s and it was as modern in 1973 as it was when it was built.

It is as modern today as when it was built.

It’s 100 years old, and it’s still modern. So modern architecture is not the problem. It’s the practitioners.

And it was dogma that led to unthinking modernism. White buildings. Horizontal slot windows. Very much the German model. It wasn’t going to go anywhere, in my view. It became a bit of a joke. People were building with 8 entry doors. Crazy post modernism. I thought: “How are people getting away with this. Those buildings are like lolly pops!”

I couldn’t stand it. I thought: “It’s all going to crash - post modernism has no future.”

José Coderch

Coderch was a totally different approach - totally modern.

We had a wonderful day together. We talked at a level architects don’t often talk at; about vulnerability and about anxiety, and I said to him: “I feel I know about design. But I don’t know how I’m going to achieve it. The anxiety has overcome me.”

He said: “Ah - we have something in common. You know I learnt many years ago, anxiety is an integral part of thinking. You must have a level of anxiety that is controllable. Every new project I am very anxious.”

Those words released me!

A small level of anxiety could be a benefit. You could harness it. I came back with a level of confidence that allowed me to be a little anxious. And I’ve retained that level of anxiety. That’s what keeps your work fresh; keeps you being young in mind and spirit and being relevant.

The past 55 years in practice has taken many turns.

Some very good. Some very difficult. Some nearly destroyed me. But I got through all of them. My greatest achievement is that I’ve survived 55 years.